Projects

The direct costs cited here estimate the change in final demand attributable to live music making in Australia in 2014. These are the costs borne by individuals in the support of live music consumption and associated activities.

To avoid double counts, intermediate inputs such as the costs of production are incorporated and not counted separately. In other words, the costs of staging live music events are assumed in the final purchase price. Similarly, the equipment, labour and utility overheads of the related merchandise providers are assumed to be fully recovered by sales.

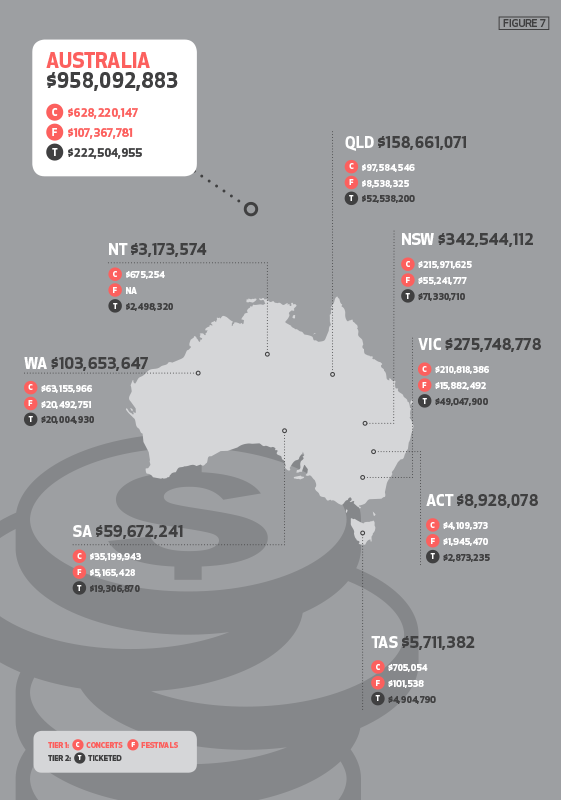

Continuing the methodology introduced in the previous section, the sum of relevant live music tickets sales is estimated in Figure 7 to be 958.1 million dollars.

Using our basic satellite account of consumption (Figure 4), which suggests that ticket sales represent 19.2 percent of total live music expenditure, we can extrapolate to estimate that in 2014 individuals directly spent 5.0 billion dollars on live music in Australia.

It should be noted that these costs are significantly broader in their coverage and greater than previous estimates of the transaction costs attributed to live music making in Australia. These departures are reasonably explained by the differences in methodology.

Importantly, our method implicitly accommodates all forms of live music making—and not just formal, venue-based production—by assuming that consumers account for this in their relative expressions of (satellite) expenditure.

The other (hopefully obvious) point to make is that these transactions are a cost, not a benefit. Studies that treat the volume of live music sales otherwise—as the majority of the ones we reviewed do—are particularly unlikely to influence the economic gatekeepers to policy reform.

It should finally be noted that this is not yet a complete accounting of costs. Live music making is subsidised by individuals, businesses and various levels of government through other venue revenue, volunteering, sponsorships, grants programs, free concerts et cetera. The sum of these investments is what is known in economics as the shadow price of, in this instance, live music production (McKean, 1968). This shadow price has the net effect of either enlarging producer profits or reducing the cost to consumers.

As such, it is a real stimulus to live music production in Australia and relevant to the scope of our enquiry. Unfortunately it was beyond our means in this instance to gather the necessary data, and the development of a more comprehensive live music satellite account is recommended as a direction for future research.